The World’s Oldest Optical Illusions

Duncan Caldwell’s further comments:

In order to provide balance, the National Geographic article mentions the "possibility... that pieces of the complete (Canecaude) spear-thrower that are now missing would clarify the image further, and show that the image is just a mammoth, plain and simple. For example, in a reconstruction in the book ‘Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age,’ authors Adrian Lister and Paul Bahn propose that the mammoth's trunk would have looped back in the lower-left part of the carving, making the lower ‘eye’ the curled up end of the mammoth's trunk."

This passage leaves readers with the impression that the two proposals are

-

-of equal weight

-

-or that an interpretation based on a missing trunk section might trump the one based on a lower eye.

This is odd because the observation of a lower eye is founded on an observable feature - the precisely carved graphic unit with apparent lids and an eyeball - while Lister and Bahn's interpretation is no more than a stretch based on a supposed section of trunk that hasn't left a trace - a stump, a fracture - nothing. In peer review the empirically supported analysis would pass muster while the conjecture would get the red pen.

More importantly, a close examination of the sculpture shows that the phantom section of trunk never existed. In order for the graphic unit that I interpret as a wisent’s eye to be interpretable, instead, as a trunk tip holding something, it would have to be clasped between ridges - the residual edges of the trunk - rising from the edge of the sculpture below, but such ridges are not present.

As if that were not enough, the edge from the base of the "trunk" to the front leg displays the same micro-denticulated silhouette as the leading edge of the back leg, where nobody would think of looking for traces of a missing trunk section and no breakage can be deduced. Instead of indicating damage, the comparable edges actually form the same pattern of parallel incisions and tiny teeth, illustrating frills of hanging fur. In the traditional reading of the Canecaude spear-thrower as a mammoth, the edge between the proboscidian’s tusk and front leg was meant to be read as the animal’s furry bib. In the sculpture’s additional reading as a bison, the same edge becomes the animal’s hairy brow.

Two more details even allow us to identify the bison’s sex and activity. Whereas the mammoth’s pupil is centered and "looks" forward, the downcast pupil of the lower eye (belonging to the bison) is a naturalistic representation of that animal’s downward gaze when it is charging with brandished horns. The size of the wisent’s hump completes the impression that one of the sculpture’s readings was meant to be an illustration of a huge, charging, and specifically male bison.

*

National Geographic’s reference to Lister and Bahn’s book encouraged me to look for a copy. The one I got was actually the older (1994) edition, which was simply entitled Mammoths. What I found shocked me. Here is the full text about the spear-thrower from the ‘94 edition: "A mammoth was selected for the decorative end of a spear-thrower from Canecaude in France (top). The tusks encircle the eye, rather like musk-ox horns" (p. 98). There's not another word about the spear-thrower in the book, and yet the caption is as telltale as a Freudian slip! The authors' realization that the crescent looked like an ungulate's horn shows that their minds were being teased and that they came within a synapse or two of seeing the image flip from a mammoth into another large "armor-headed" herbivore: a bison or musk-ox. If only they'd put the notion of the ungulate horn together with the lower eye!

But they didn't. And when they revised their book, they apparently explained away the germ stirring in the back of their minds by imagining a ghostly section of missing trunk. The mind is a slippery thing, and sometimes explains things away all too easily. I know mine does, all the time.

*

While looking for Lister and Bahn’s book, I came across another description of the Canecaude sculpture, which showed that yet another observer had come within a synapse of seeing the image flip from the image we’ve been told to see, that of a mammoth, to the alternative reading of a bison. This time it was another brilliant prehistorian, Randall White, who noted the following in his beautiful book, Prehistoric Art: The symbolic journey of humankind: “Strangely, the ears were not represented and the tusks, in form and location, are more like bovid horns” (2003. p. 105 fig. 72).

Precisely! The reason the “tusk” (there is actually only one) resembles a horn is because it had to look both like a tusk and a horn. The reason there is no mammoth ear is because it would have destroyed the bison reading. The whole sculpture is a tour-de-force of compromises and solutions, including the unusual positioning of the mammoth’s eye so much lower than the “tusk’s” root, to make both readings possible. In the terminology of art historians and the fine arts, the sculptor was just as much a master as any artist of the modern era. But what a tease!

*

Ironically, the more anatomically correct of the two eyes is actually the lower one belonging to the bison, not to the upper "mammoth" one, which, as I said above, isn’t where it would normally be – well above the tusk’s root – but lower, where we find it strangely squeezed between the crescent and edge of the sculpture. The sculptor was pushing his (or her) impressionistic magic to the limit by placing that eye just outside the "tusk’s" upper edge, but obviously succeeded in conveying the idea of a mammoth all the same, since the image has continued to be read that way in modern times.

Even so, if one wanted to take issue with one of the two readings (and, of course, I champion both), it would have to be with the idea that this sculpture represents a mammoth, rather than with the more anatomically faithful reading of it as a bison. Furthermore, the very fact that the artist was making a bison - whose cephalic hump wasn’t quite large enough to allow the carver to place a mammoth eye above the tusk root - is what forced the sculptor to fudge the position of the graphic unit that we still read as a proboscidian eye. What a master!

*

Another red herring of an argument against the bison can be dismissed just as readily as the idea that the bottom eye actually represented the tip of the trunk - the notion that the top of its head is a crack post-dating the object's manufacture. The top of the bison's head is clearly formed both by the tusk-horn crescent, which is incontestably anthropogenic, and by the exaggerated cephalic hump that it shares with the mammoth - a device also used in the Font-de-Gaume repertoire.

*

Although they may not rise to the level of perfect optical illusions, it is also important to note that Paleolithic carvers created visual puns that combined references to male and female sexual attributes. These puns range from a wand found at le Placard, which looks like a phallus and scrotum until one sees that it has a vulva between stumps at the base, to another wand from Dolni Vestonice with twin lumps that can be read either as breasts or testicles. Similar sexual amalgams have been suggested for the Lespugue and Savigano Venuses, most recently in an article that I wrote for the Barbier-Mueller Museum called "Supernatural Pregnancies: Common features and new ideas concerning Upper Paleolithic feminine imagery" (2010, Arts & Cultures: pages 52-75).

It should also be noted that several other authors, including Lothar Zoltz (1951. “Idoles paléolithiques de l’être androgyne”. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, pp. 333-340) have discussed ambiguous objects and images like the ones illustrated in the article on the Ségognole bison that gave rise to National Geographic’s report, although none of them identified the specific images I dealt with.

One of the most recent and comprehensive of the authors to discuss the subject before me is Barbara Olins Alpert, whose work I discovered when we met at the very conference where I gave the paper that underlies Nat Geo’s article. When I mentioned during our meeting that one of the themes of my paper was Paleolithic images that play upon similarities in the silhouettes of bison and mammoths, Barbara responded that she’d also written on Paleolithic figure-ground reversals, and showed me a magnificent book that Foundation 20 21 had brought out in 2008: The Creative Ice Age Brain: Cave Art in the Light of Neuroscience. When she later sent me a copy, I discovered a fascinating chapter called “Ambiguity: Playing with Multiple Meanings” in which she illustrates two quadrupeds from “Laugerie” that face each other upside-down, making it difficult to see one while seeing the other (p. 121), a bison from Castillo whose tail becomes the following ones horn (p. 128), two horse heads that share a mane from Les Combarelles (p. 133), and the famous interwoven images of a headless woman and facial profile, in which breasts double as eyes, which was reported in 1976 by L. Pales and M. Tassin de Saint-Péreuse (Les gravures de La Marche, Tome 2: Les humains. Paris, Ophrys).

Some of these images might not rise to the level of true optical illusions as defined by the authority that Nat Geo consulted on the matter, Nigel Warburton, but, together with hundreds of other examples where observers have shown that Paleolithic artists re-used a line or graphic unit to form part of a second or third figure, they prove that the Ice Age’s economical artists often compressed paradoxical images and ideas by playing upon the ambiguities of perception.

*

Although this is neither in the Nat Geo piece nor my underlying article, the use of recognizable figure-ground illusions during the Upper Paleolithic suggests that the mind had evolved to the point where it could incorporate similar gestalt shifts in the deepest structure of languages and thought. I only wish that Steven Pinker had known of the bison-mammoth shifts when he was writing about similar ones in English in a section of "The Stuff of Thought” that he called “Flipping the Frame” (pg 42-51).

*

Finally, Chandrachoodan Gopalakrishnan, who saw the report on National Geographic, informed Andrew Howley and myself that a remarkable equivalent of the Paleolithic mammoth-bison optical illusion exists in Tamil Nadu, India, where bas-reliefs in temples show bull and elephant bodies, which share the same head. The head is sculpted in such a way that it can be read first in one direction, as a bull’s, then in the other, as an elephant’s. The Paleolithic puns on bovines and proboscidians are so far apart from the Indian ones in both place and time that links between them are a tremendous long shot, but the possibility can’t be discounted entirely. First one would have to determine how old the theme is in India. Then one should probably look for antecedents to the north, since any connection between the Paleolithic and modern examples must have come across the steppes.

In the meantime, it would be fascinating to learn more about the stories, beliefs and practices surrounding the Indian amalgams between bulls and elephants.

Please click on the following thumbnail photos, which I’ve used as icons, to see the web pages or PDFs described in the captions.

The “prey-mother” hypothesis concerning Paleolithic feminine imagery & venus figurines

The Foz Coa / Coa Valley prehistoric rock art scandal

Prehistoric Art Emergency & Foz Coa / Coa Valley home page

PDF: The Coa Valley prehistoric rock art scandal - An investigation & call to arms. (1995)

A Murder, Bombing, and Trip to “Dolmens”

Archaeological tours

Key words: Human evolution; Neandertal extinction; The Neanderthal insulation hypothesis; Baby sling adaptations; The baby-sling hypothesis for human body baldness, Paleolithic venus / venuses; The “prey-mother” hypothesis - A new interpretation of Paleolithic feminine imagery; Archaeological & prehistoric art cave tours; Testimonials; Prehistoric phalangeal figurines; Neanderthal extinction; Alan Dershowitz; Dan Burstein, Secrets of the Code; Marine and Paleobiological Research Institute (MPRI); New Dominion Pictures; GREPAL; Gaumont; Wellspring Museum; Neanderthal / Neandertal adaptations and extinction; Architecture & landscape design; Neanderthal diet; Neanderthal behavior; Evolution of large brains; Balkan prehistory; Vinca, Lepenski Vir; Martha’s Vineyard Community Services Possible Dreams auction; Robert Bednarik; Rock Art Research; Susiluola (Wolf) Cave, Lappfjärd, Finland; paleontology museum in Paris / Montmartre quarries; Neolithic mortuary monuments; Dolmens; Prehistoric French sites; Cave art; Prehistoric art; World’s oldest

In a paper presented at the IFRAO Congress on Pleistocene Art of the World, in Sept. 2010, I unveiled several types of Paleolithic imagery that seem intended to be recognized in phases.

The following article from National Geographic’s web site examined one aspect of the IFRAO paper – one of the world’s oldest known true optical illusions and a number of related images that play on similarities between the contours of bison and mammoths.

I have added comments about the article and further observations, confirming the analysis, at the end.

***

World's Oldest Optical Illusion Found?

By Andrew Howley

Published on NatGeo News Watch: News Editor David Braun’s Eye on the World

Tags: Andrew Howley, caves, Europe, France, human origins, optical illusions, paleolithic art, philosophy, rock art

Categories: Archaeology, Cultures

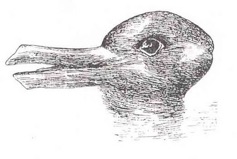

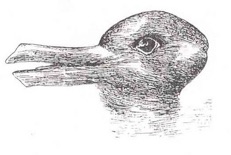

Long before the famous duck-rabbit illusion (seen at right), prehistoric artists were creating mind-bending double images of their own, according to a new paper presented earlier this year at an international convention on rock art research.

The paper's author, Duncan Caldwell has surveyed the Paleolithic art of several caves in France and discovered a recurring theme that he says can't be simply accidental. Throughout the cave of Font-de-Gaume, and in examples from other sites as well, drawings and engravings of woolly mammoths and bison often share certain lines or other features, creating overlapping images that can be read first as one animal, then the other. Rarely, if ever, do they do the same with other animals.

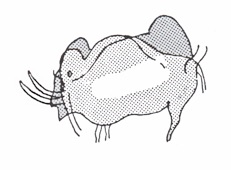

While images of horses, deer, extinct cattle, and even rhinos often appear in such caves, and often partially or entirely overlap each other, it is only the mammoth-bison pair that Caldwell found regularly appearing superimposed so exactly. For example in the modern drawing below of an image from Font-de-Gaume, one main body shape, underbelly, and set of legs is adorned with signs of both mammoth and bison heads at both ends. These two large, bulbous, "armor-headed herbivores" which share many physical similarities in life, seem to have had some connection for people in this region in art as well.

Early cave art researcher Henri Breuil copied this image of overlapping bison and mammoth from the walls of Font-de-Gaume in France. (Image courtesy of Duncan Caldwell)

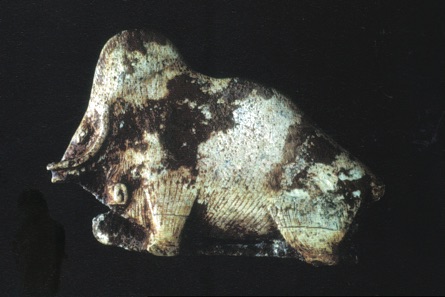

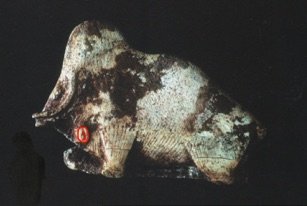

In a particularly striking example, a small figurine has been given the details of a bison on one side and those of a mammoth on the other. The Paleolithic artist was clearly playing with the similar contours of the two animals and creating a single object that could be flipped to represent one species or the other.

The two sides of a figurine from a site near Cambrai show very different details. On one side (left), the high back leg and short front leg are characteristic of depictions of bison. On the other, the tall straight front leg and grooves depicting long hair in the midriff are typical of mammoths. (Image courtesy of Duncan Caldwell)

Nice Trick, But Is It an Illusion?

There's a big difference between overlapping images or ambiguous profiles and a proper optical illusion however. Nigel Warburton is a senior lecturer of philosophy at The Open University and co-host of the podcast "Philosophy Bites," which uses the duck-rabbit as its logo. For him, knowing the original context of the image is key. Speaking of the classic version, he said "If somebody had been illustrating a children's book about rabbits, nobody would have seen it as a duck." As he put it, "the fact that a figure can be read in two ways isn't conclusive proof that it was intended to be read both ways."

A classic version of the duck-rabbit illustration, contemplated by psychologist Joseph Jastrow in 1899, and philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in 1953. (wikimedia commons)

Another classic shape-shifting image is the "Old Woman-Young Woman" image, where the young woman's neckband and ear become the old woman's mouth and eye, respectively. (wikimedia commons)

The duck-rabbit is different because we know that it was created not just to show both animals individually, but to call attention to the strange sensation of one replacing the other. It's to some degree a "reflection on the nature of perception." The mammoth-bison images clearly make use of ambiguous shapes and similarities between the animals, but that doesn't guarantee they were intended as optical illusions.

Magic Is in the Beholder of the Eye

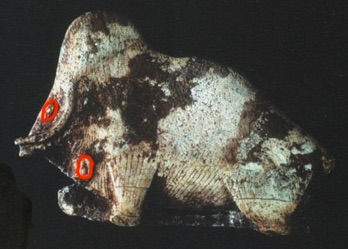

Perhaps the most dramatic candidate for a mammoth-bison image meeting this requirement and being an intentional illusion isn't on a cave wall, but on a carving from a spear-thrower from the site of Canecaude. In this piece, as Caldwell sees it, it's not that the animals share a contour or a few lines, but that just two small details allow the entire image to be read as either of the two species, and seeing one causes the other to "disappear."

Unlike other bison-mammoths that depict two distinct but overlapping images, this carving from a spear-thrower features one image that can be seen two different ways. The photo at the top of the page show the artifact in its actual condition. The eyes above and below the crescent, which serves both as a mammoth’s tusk (for the upper eye) and bison’s horn (for the lower eye) are highlighted in red in the photo on the right. (Images courtesy of Duncan Caldwell)

The details in question are the eyes. Caldwell describes how there is "both an upper eye, which turns the crescent beneath it into a tusk, and lower eye, beside the front leg, that transforms the same crescent which we just interpreted as a "tusk", into a bison's overhead horn." Looking back and forth between the eyes then, we are able to see the entire shape transform from one animal to the other, an effect much more like the classic Gestalt shift of the duck-rabbit.

Significantly, it is hard to think of other reasons for the unusual position of the eyes. First of all, their delicately carved shapes show that they were made intentionally, and are not just accidental markings. Secondly, the details of the body of the animal, its tusk/horns, long hair, and legs are all fairly realistically represented showing the artist's ability to make an accurate full profile view if desired.

Even in the somewhat common technique in prehistoric art of using "twisted perspective" where an animal's body will be shown in profile, but both eyes will be visible on the face in a Picasso-like manner, the eyes are generally still close together. In addition, that technique seems to be more common in flat wall art than in full sculpture, where the ability to put one eye on each side of the sculpture takes care of the perspective problem.

The possibility remains however that pieces of the complete spear-thrower that are now missing would clarify the image further, and show that the image is just a mammoth, plain and simple. For example, in a reconstruction in the book "Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age," authors Adrian Lister and Paul Bahn propose that the mammoth's trunk would have looped back in the lower-left part of the carving, making the lower "eye" the curled up end of the mammoth's trunk.

A Window Into Stone Age Philosophy?

If Caldwell's analysis of the mammoth-bison phenomenon is correct, we begin to get a view not only of what prehistoric people saw, but also how they thought, and that has the potential to change our perspective and how we see other artifacts as well.

That perspective shift is also what makes these ambiguity illusions so appealing in the first place. Nigel Warburton said he chose the duck-rabbit as the logo for "Philosophy Bites" because it's also what he likes about philosophy itself. "Part of what philosophy does," he said "is, sometimes, make you see what you already knew in a completely different light." Perhaps someone enjoyed the same thought sitting in a cave, some 15,000 years ago.

(Updated 12/23/2010)

For More Information

Duncan Caldwell is a fellow at the Marine and Paleobiological Research Institute in Massachusetts.

Nigel Warburton is a Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at The Open University. His latest book, "Philosophy Bites," based on the podcasts of the same name, is available from Oxford University Press.

Andrew Howley is a senior producer for National Geographic Digital Media. He manages and edits the home pages of nationalgeographic.com and National Geographic Daily News, and contributes largely to the Society's Facebook page, which has more than 3.8 million followers. He studied anthropology with a focus on archaeology at the College of William & Mary in Virginia.

One month after National Geographic posted the above article on its site, its author, Andrew Howley, reported that it had “crested 100,000 page views” while receiving 2,780 likes on Nat Geo’s Facebook page.

Key words: Oldest optical illusion, National Geographic, Duncan Caldwell, Paleolithic art, Font-de-Gaume, Cave art,

Top left: The mammoth eye in red. Top right: the bison eye in red. Bottom left: The mammoth eye exposed (on a replica). Bottom right: The bison eye exposed on a replica.