The “Prey-Mother” Hypothesis -

A New Interpretation of Paleolithic Feminine Imagery

Fig. 1 - An untouched photograph of a pregnant therianthropomorph, known as the “Femme au Renne”. Laugerie-Basse rock shelter, Dordogne. Engraving on reindeer antler, 101 mm x 65 mm. Musée des Antiquités Nationales, Saint-Germain-en-Laye (Inv. No. 47 001).

My most recent articles to delve into the significance of Paleolithic feminine imagery are:

-

-“Supernatural Pregnancies”1, which was published in the English, French and Spanish, 2010 editions of Arts & Cultures - a book published annually by the Barbier-Mueller Museums of Geneva and Barcelona,

-

-and a long peer-reviewed article entitled “The Identification of the First Palaeolithic Animal Sculpture in the Ile-de-France: The Ségognole 3 Bison and its Ramifications” (see the PDF links below), which was presented on September 6th, 2010 at the International Federation of Rock Art Organizations’ Congress on Pleistocene art of the world and published in its Acts (Pleistocene Art of the World, ISBN 987-2-9531148-3-6).

Along with an earlier peer-reviewed paper on the implications of the simplest paleolithic feminine figurines2, both of these articles built a case for a new interpretation of a large part of the Paleolithic feminine canon. This re-interpretation, which could be dubbed the “Prey-Mother” hypothesis, is based on new readings of such iconic works of Paleolithic art as the “Femme au Renne” from Laugerie-Basse (Figs. 1-3) and the engraving of a pregnant therianthropomorph following a horse from Étiolles (Fig. 4). Although the new theory is based on internal evidence, it is also in keeping with women’s known roles in cold-weather “hunter-gatherer” - or, as I prefer to call them, hunter-sewer economies.

Frequently, one of these roles is to increase the chance of a hunter’s success by supernaturally providing him with animal qualities. Several polar cultures believe wives do this while sewing their husbands’ weatherproof clothing and camouflage by synthesizing the powers of the species whose hides compose the garments, thereby imbuing their husbands with animal qualities needed for success. Another common role is for wives to enter trances in which they “become” their husbands’ prey and lull it into coming within range. A third is to reconcile hunters with animals they have killed by “feeding” dead animals like honored guests and inviting them upon their “departure” to return where they came from as new, living creatures. “Whale-wives” among the Koryaks and Nootka, for example, do this by supernaturally initiating the regeneration of harpooned whales. All three roles involve beliefs in a woman’s maternal capacity not only to give birth to humans but also to morph into, control and generate the largest and most socially and symbolically important prey species.*

There is evidence that horses and large “armor-headed” herbivores - mammoths in the north and usually bison in the south - filled these roles during the Eurasian Upper Paleolithic and were associated with extremely gravid “women” who have zoomorphic traits and connections – through umbilical lines from their vulvas or identical markings - to animals, which may be variously interpreted as animal-doubles, animal-husbands or animal-progeny. Surprisingly, all three roles are consistent with such ethnographically observed customs as the “whale-wife-mothers”.

Some Paleolithic feminine images, like the pregnant figure with a herbivore’s head and woman’s pregnant body from Étiolles (Fig. 4), seem to be connected to animals umbilically - in this case with a horse. Another engraving – this time in the one from Laugerie-Basse (Fig. 1) - has always been interpreted as showing a pregnant woman under a large male herbivore - already a provocative image. But a closer examination reveals several more layers of information, the first of which prove that the gravid figure is hardly just a "woman".

The first clue is a change of angle in her shins from one side of the fragmentary herbivore’s fetlocks to the other, leading us to find faint incisions across the fetlocks that confirm the impression that the pregnant figure has hocks (Fig. 2, highlighted in blue). Another clue that the figure isn’t as human as we thought lies in the fact that both the leg of the reindeer or bison straddling her and the lower half of her body are covered with identical fur patterns (Fig. 2, purple). Put her hocks and fur together and it's clear that the pregnant figure is really partly zoomorphic, making her what prehistorians call a therianthropomorph!

But the engraving has even more secrets. First, two lightly incised hoops (Fig. 2, orange) arch over the therianthropomorph's belly, faithfully echoing the more heavily incised curve of the realistically portrayed pregnancy with outer dimensions that seem to be ballooning pulsations or supernaturally large “pregnancies” towards the reindeer or bison.

The fur on her pregnant belly and legs, which is incised in the same way as the fur on the animal’s leg, is shown without enhancement in figure 1 - but is highlighted here in purple.

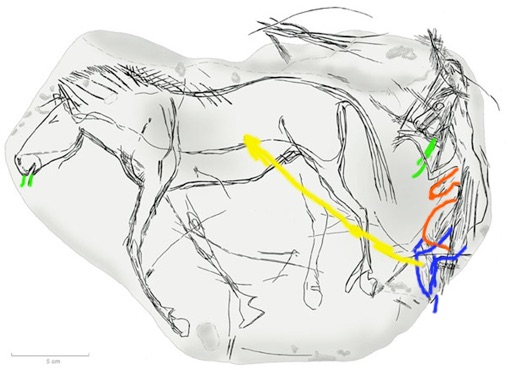

Two larger-than-life dimensions, echoing the deeply engraved contour of the “woman’s” realistically swollen belly, are shown here in orange.

Next, the engraving contains two features that were probably only intended to be seen even later that the 2 arches - for example, after a further degree of initiation. The first is a probable baby (Fig. 3, blue), which may not have been noticed since the Paleolithic. Its head, which is composed of a semi-circle of fine cross-hatches, rests within the bubble formed by the extra dimensions above the “woman’s” swollen belly. The two lines arching over the pregnancy contain their own discrete secondary feature – an eyed snake whose tail issues umbilically from the “woman’s” vulva (Fig. 3, orange). The back of the snake’s head is be evidenced by slight shifts in the ballooning lines over the belly while its snout and mouth actually touch the circular pattern that seems to be a baby’s head.

The last feature that I’ve been able to interpret is a “stream” of 4 largely parallel lines (Fig. 3, yellow) from the tip of the overhead herbivore’s penal sheath down to the point on the upper arch that corresponds to the back of the snake’s head. The graphic unit obviously represents one or more of the literal projections from such a sheath; in other words, urination, insemination or an erect phallus. But a complementary interpretation is suggested both by the fact that arched snakes are equated with rainbows from Angola (among the Chokwe) to Australia and the resemblance of the 4 slanting lines to distant rain**. If this reading is correct, then the imagery reflected beliefs, which at one of their deepest levels, encompassed the earth, sky and weather in between, making this possibly the oldest known image to include references to the heavens.

Fig. 3 - La Femme au Renne. The most legible lines of a probable baby on top of the “woman” are shown in blue. The part of the double arch over the pregnancy that can be read as a snake touching the baby’s head is shown here in orange. The “stream” of 4 parallel slanting lines from the herbivore’s penal sheath to the back of the snake’s head are highlighted in yellow. Could this imagery, at one level, illustrate the oldest known “rainbow serpent” and inseminating rain? (Caldwell)

Together, the complex imagery of this engraving suggests equally layered beliefs concerning the relationship between women’s pregnancies and the animal world. The pregnancy here has supernatural dimensions that encompass the phantasmal, lightly incised, dotted “baby” while pulsing towards the herbivore overhead. But the pregnancy’s larger-than-life dimensions also contain the possible umbilical serpent, which may be associated, like umbilical cords, with humanity’s original connections and ineluctable separations. At the heart of this polysemic image involving literal births, supernatural transformations, and cycles of life and death probably lies a belief that women had the capacity to generate and intercede among humans and their prey - making them the sex that spiritually controlled the food supply.

Fig. 4 - A pregnant therianthropomorph with a herbivore’s head and high rear leg, but a woman’s breast and pregnant belly, linked “umbilically” to a horse, which is performing the same action, with lines issuing from both figures’ mouths. Magdalenian. Étiolles, France. After Taborin et al. 20003; Taborin et al. 20014; Olive et al. 20035.

-

*Beliefs and rituals that associate women in their maternal capacity with symbolically and socially important prey are found south of the circumpolar regions too. During the Ainu Bear Festival, for example, “a bear cub, after being captured, is put in a cage and fed, while the people parade around it invoking the gods. Then they secure and strangle the bear with poles and cut off its head with a sword, while the woman who had been wet nurse to the cub cries” (my italics) (Severin, Timothy. 1973. The Horizon Book of Vanishing Primitive Man. p. 234).

Here’s another example, which comes from below the equator: After boys of the dugong clan in the Torres Strait have speared their clan’s totem animal as part of their initiation into manhood, the clan’s women symbolically suckle the slain dugong while moaning their grief during the Zug Ngurrpai ceremony.

** One of the most beautiful evocations of this widespread family of myths comes from Wade Davis’s book about his search for a zombi poison and its antidote in Haiti, “The Serpent and the Rainbow”: “‘Ayida Wedo!’ someone called, his shout a whisper. It was true. Mist fell over the basin, and the water splintered the sunlight, leaving a rainbow arched across the entire face of the waterfall. It was the goddess of many colors, delicate and ephemeral, come to rejoice with her mate. Ayida Wedo the Rainbow and Damballah the Serpent, the father of the falling waters and the reservoir of all spiritual wisdom.” (The Serpent and the Rainbow. 1985. Warner Books. pp. 212-213)

Here’s another example - this time from Australia: “Initiates in the rainbow serpent totem produce the sacred opals that symbolize his joining of the water and sky, and in their dances shake bird’s down into the air to imitate rain-bearing clouds” (Severin, Timothy. 1973. The Horizon Book of Vanishing Primitive Man. p. 61).

1 Caldwell, D. (2010) Supernatural Pregnancies: Common features and new ideas concerning Upper Paleolithic feminine imagery. Arts & Cultures, Barbier-Mueller Museum, Geneva. pp. 52-75

2 Caldwell, D. (2009) Palaeolithic Whistles or Figurines? A preliminary survey of pre-historic phalangeal figurines. Rock Art Research, Vol. 26, No. 1: 65-82 (Also see the page on this site dedicated to the work of Pascal Raux - the father of the Phalangeal Figurine Hypothesis)

3 Olive, M., N. Pigeot, Y. Taborin, G. Tosello and M. Philippe (2003) Lorsque le galet gravé paraît. Les témoins symboliques à Etiolles (Essonnes). In Sens dessus dessous. La recherche du sens en Préhistoire. Recueil de textes offerts à Jean Leclerc & Claude Masset. Revue archéologique de Picardie, Senlis.

4 Taborin, Y., M. Christensen, M. Olive, N. Pigeot, C. Fritz and G. Tosello (2001) De l’art magdalénien figuratif à Etiolles (Essonne, Bassin Parisien). Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 98(1): 125–132.

5 Taborin, Y., M. Olive, N. Pigeot and M. Christensen (2000) Le site magdalénien d’Etiolles: bilan des fouilles de 1998–1999–2000. Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique de Corbeil, de l’Essonne et du Hurepoix 70: 107–120.

© 2009 Duncan Caldwell