The presentation in the

Planetarium of the

California Academy of Sciences unraveled one of the last mysteries of Tutankhamun’s tomb by explaining how the Egyptians of his dynasty obtained a piece of glass created by a colossal meteorite impact or unique ejection from the planet’s core from a zone that had already become the closest thing to Mars on Earth. A place so hostile that they couldn’t reach it even if they had camels. Which they didn’t: all the ancient Egyptians had was donkeys. Nobody has ever been able to explain – and prove – how Tut’s jewelers obtained the world’s purest natural glass that they used to make the scarab in the middle of one of his breastplates - glass so strange that it is filled with nano-diamonds, iridium, stishovite and other apparent evidence of a meteoritic collision. Until now.

The lecture revealed the discoveries of an expedition in March 2006 that sought to answer the enigma – an expedition that bore its ultimate fruit only when it became stranded without fuel or water during a solar eclipse, allowing the team one last opportunity to prospect for an archaeological site that might provide the missing link, while hoping for rescue.

The presentation unveiled two major discoveries.

First, of prehistoric tool factories that specialized in making Libyan Desert Glass tools on such an industrialized scale during the Holocene Wet Phase (12,500–5,300 cal. B.C.E.), that they had to be exporting their products over a much larger zone than the one where the glass occurs naturally.

And, two, the discovery of a series of prehistoric sites covered with glass tools, which were exported beyond the glass's natural distribution during the Sahara’s wet phases – including an eight-to-ten-thousand-year-old site, over 250 miles from the "factories", at a pigment quarry where an expedition from Tut’s time (the late 18th Dynasty) left its characteristic shards.

In other words, the expedition proved that Tut’s prospectors could have found the glass, which his jewelers used to make the sun symbol that they put on the solar plexus of their living god, on a site that was already thousands of years old. In doing so, the expedition also revealed one of the reasons that the Egyptians were struggling to penetrate the desert against great odds with donkey caravans - they were searching for and scouring prehistoric sites for a material so rare and strange that they believed it was solidified sunlight itself.

On a less sexy note, the expedition’s discovery of Aterian, Mesolithic, pre-ceramic Neolithic and mid-Neolithic anthropic glass sites hundreds of kilometers outside the natural zone shows that long-range exchange and distribution systems for the exotic material sprang up both during the Holocene Wet Phase and the Aterian tradition, which lasted from 80,000 to 30,000 years ago.

D. Caldwell & E. Honoré at the briefing that I gave before entering the desert to define the expedition’s goals & destinations, which I’d set based on solo reconnaissance in 2005.

Base camp in a closed inter-dune corridor of the Great Sand Sea

D. Caldwell, K. Compton & S. Schwab mapping a Holocene Wet Phase Desert Glass tool factory

GREPAL archaeologists L. Watrin & E. Honoré mapping a Desert Glass tool workshop with an expedition volunteer, K. Compton

One of the Desert Glass nodule caches at the main Holocene Wet Phase tool factory site

Volunteer, S. Schwab, brushing off a nodule cache for mapping at the main factory site

Egyptologist, L. Watrin, directs mapping of the vast tool factory. Note the two nodule caches and a hearth in the background.

Egyptologist, L. Watrin, holding one of the glass points found at the knapping stations of the main tool factory site.

Peripheral site 1: This Neolithic site, which appears on both sides of a dune on the southern edge of the Gilf el Khebir, has Desert Glass tools which have been transported hundreds of kilometers south of the material’s natural range. Note the fragment of a grain grinding quern. ca. 8,000 BP.

Peripheral Glass site 2, which is nearby, is Aterian, meaning that the glass at the site was exported from its natural zone far to the north around 30,000 years ago. Note the Aterian point.

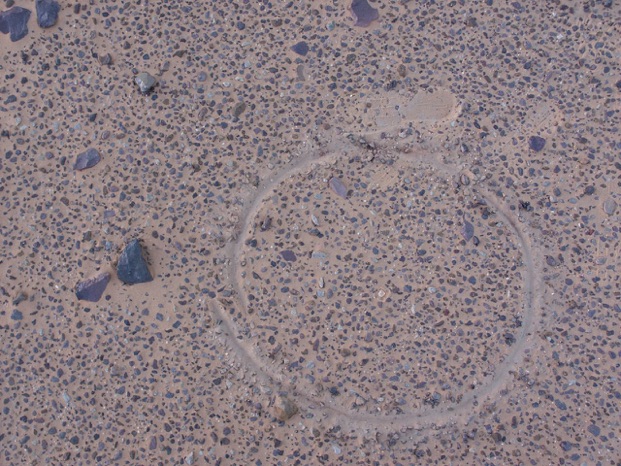

A piece of Libyan Desert Glass can be seen at the center of the circle at Peripheral Glass site 2 on the southern Gilf beside Aterian tools & debitage.

D. Caldwell & K. Compton prospecting for peripheral glass sites on the southern brink of the Gilf el Khebir plateau.

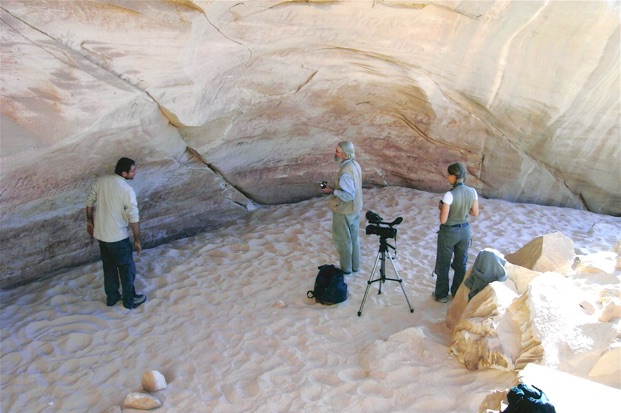

L. Watrin, D. Caldwell & E. Honoré at work in the Cave of the Headless Beast, aka Wadi Sora II.

Peripheral Site 4 is within 4 miles of this pigment outcropping on the Abu Ballas donkey trail. The Desert Glass tools at the site were transported over 250 miles from the natural source of the glass to this site, where they are in close proximity to shards from the Late 18th Dynasty, which encompassed Tut’s reign.

The expedition’s ATVs above the Pharaonic water depositary at Abu Ballas, which contains shards from Tut’s time.

Please click on the following thumbnail photos, which I’ve used as icons, to see the web pages or PDFs described in the captions.

PDF: Western Saharan Sculptural Families and the Possible Origins of the Osiris-Horus Cycle, Rock Art Research, 2013, Vol. 30, No. 2 (November): 174-196.

Please click on this icon to watch “The Saharan Origins of Ancient Egyptian Royal Symbols”. I gave this version of the lecture at The Explorers Club in New York on May 20, 2013. In passing, I apologize for mis-speaking at one point and saying that the New Kingdom was 1200 BP, when I meant BC.

Copyright Duncan Caldwell 2006 & 2013, all rights reserved