A MURDER, BOMBING AND

EXCURSION AMONG DOLMENS

Duncan Caldwell

© 1996 Duncan Caldwell

Although the field trip for archaeologists to the Neolithic tombs of the Vexin region, northwest of Paris, didn't start with a murder, it got off to a bad start. As the coach veered onto a highway, some of the prehistorians in the back yelled that the box with our food was still on the curb. The bus lurched to a halt and the area’s chief archaeologist darted from the seat beside me to face down trucks and retrieve our picnics.

Flustered, we set forth again.

Having much to learn, I’d enthroned myself in the front row to drink in new landscapes before he’d even boarded the bus, and been happily surprised when the greatest authority on local mortuary customs at the dawn of agriculture sat in the guide’s seat, between me and the driver. Although I was perfectly positioned to start peppering him with questions and get a personalized tour, I kept my peace at first as high-rises gave way to fields and the bus trundled towards the first megalithic monument on our itinerary - an allée couverte or "covered alley", which is basically a huge crypt made out of stone slabs in a trench, whereas dolmens were similar tombs built on the surface, before being covered with dirt.

The township of Guiry-en-Vexin, where the allée couverte is embedded in a ridge overlooking orchards and a village dominated by a chateau, was one of the few places where I’d been kicked off land while looking for prehistoric sites. A tattered gamekeeper had nabbed me along with a friend and herded us through rows of sprouts towards a Jaguar hidden within a tree line, mumbling that he had to do it because his lord had his binoculars trained on us. The vigilant aristocrat was costumed in "country" tweeds and accosted me with matching hauteur and severity, only to be caught off guard by my foreign accent, smiling greeting and stretched hand - such blithe innocence and egalitarian presumption!

Still, there was a certain satisfaction in bagging such nervy and exotic game as myself, so he let us off with a duel of barbed wit, which I fought sportingly, though it was prudent to lose. Still, I was glad to be coming back under official auspices.

When we arrived, the allée couverte’s roofed chamber and forecourt of giant slabs were webbed with surveyor's string, but we ducked the filaments to examine twinned protuberances above raised crescents on boulders standing upright on either side of a "manhole" entrance. Here, in relief, were the Neolithic goddess’s eroded breasts and necklaces: one of a long series of female supernaturals who had reigned in various emanations from the Atlantic to the Fertile Crescent from the Aurignacian, 35,000 years ago, to at least the end of the Neolithic, 4,500 years ago, and even later on island redoubts in the Mediterranean. The images of these supernaturals range from a few dozen 25,000-year-old Gravettian “venuses”, such as the famous one from Willendorf, to the stocky matrons of Catal Huyuk and Malta, 20,000 years later - and yet such feminine imagery is so rarely found at French Neolithic sites that this was a treat.

After crawling into the chamber where the deity’s wards had lain pell-mell in her community of death, the pensive company returned to our vehicles mulling ancient profundities - only to be confronted by a vigilante furiously scribbling down license plates. "I'm calling the gendarmes," shouted the mayor's tall brother in his gray suit, "I don't care if that thing is a national monument and you are on one of your official visits, the shoulder is municipal, not national, property!"

We all scrambled aboard the coach and ogled the altercation through its tinted windows like cowed aquarium fish, to see if our guide could save the day again. Finally, he seemed to win us a moment's grace - or at least a head start - and jumped aboard, spurring the driver to step on it, while leaning forward, gripping the rail. "Why," I ventured, after we had put some distance behind us, "is the mayor's family harassing the staff of the very museum that put their village on the map?"

"Well," the great prehistorian turned to me beleagueredly, "actually the present mayor isn't the mayor who invited us to build the museum in Guiry. He's our sponsor's opponent and is allied to this nobleman" (the nobleman!) "who bought the chateau a few years ago and tipped the following election by winning over a few large families. Now the nobleman's pet mayor is so opposed to his predecessor's legacy that he calls meetings empowered to expropriate property for the precise hours that the museum is inaugurating an exhibition, just to make sure nobody dares attend openings."

Damned, if they weren’t trying to smoke the archeologists out of their hole!

We made haste down the length of a plateau that forms the spine of the Vexin region. Our route lay parallel to an equally straight Roman road, the Chaussée de Jules César, heading for the river Epte, and the English Channel beyond it. That ancient military road had once strung together a series of Roman farms, which had vanished except for concentrations of shards. Further out, along the plateau's edges, the savannah of wheat also hid scatterings of flint where Neolithic camps had overlooked valleys. Everything had been swept under vast rugs of greenery.

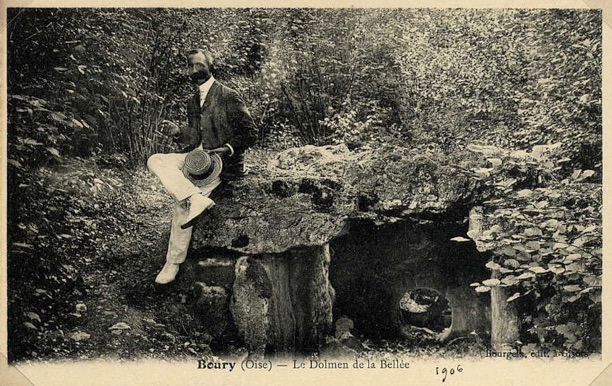

Ahead lay the next covered alley - "La Bellée" at Boury-en-Vexin. The coach brushed crops aside as it trundled incongruously along lanes too narrow for its chromed monstrosity, but so much isolation and verdure promised safety from civilization's sour notes. Finally, the copse harboring the megaliths arose from an approaching ridge. But, oddly, a blue car was parked across the dirt road. A cop car? What with spy satellites and cellular phones, the world had just gotten too quick for us. Still, we disembarked in a milling throng, hoping to brazen it out. But the stone-faced policeman neither budged nor arrested us. All he did was make it painfully clear that nobody but nobody was going to take a step forward.

But why? He ignored all queries.

Our permits meant nothing. We strained to discern what was going on. Among the trees, men in lab coats ferreted around the giant slabs. Our cop's radio crackled and we made out.... that there was a bullet-ridden body inside! Dumped? A suicide? Maybe not! And the cop wasn't even arresting us? Wasn't it a bit too coincidental that an entire coach-load of bone analysts had appeared - for the first official visit of the allée couverte in 75 years - when the funeral monument’s contents had just been refreshed? If this plot had been written by Agatha Christie, the constabulary would have rounded up the whole scruffy lot of us and quarantined our band in a chateau, even as the perpetrator continued to strike, reducing our numbers, until some shrewd detective or coolly analytical archaeologist broke the case while there were still enough suspects to make it worth his while. Luckily the guard didn't realize the obvious as we made our second get-away.

The accumulation of events was growing so bizarre that it smelled fishily like fate was ripening aboard our bus like a heady cheese. Everyone grinned uneasily and began to exchange egregious wisecracks, breaking the last ice between us. Our bus had become the Flying Dutchman - and we its crew!

Next stop was for lunch: a picnic in a tame municipal park beside the Seine. The chateau from which Rommel had directed Nazi counter-attacks during the Battle of Normandy loomed above the sliver of a town on la Roche-Guyon – Guyon Rock. Our plastic trays laden with roast beef, grated vegetables and mounds of mayonnaise were laid out on a parapet. But where were the forks and knives? Forgotten! A lucky few gnawed morsels off the tips of their jackknives - but the rest of us had to prune twigs from the municipal plantings and whittle chopsticks. Soon we were eating Chinese-style and climbed back on the bus like a plague of locusts, having stripped the bushes.

The next two visits to mortuary monuments were actually uneventful (if you don't count the fact that the bus drove away at the first one so as to give any gendarmes a moving target, and that inventive vandals had painted and fired upon a bull’s-eye dead center on the standing stone at the end of the second covered alley). Basically, though, we were able to concentrate again on faint engravings, constricting budgets, dating cultures and splitting archaeological hairs, and, so, we’d recovered some of our air of professionalism as we headed for the last stop, a complex of three covered alleys that had become my own stomping ground.

When the band poured out onto the shoulder on the plateau above Presles-Courcelles in the Oise region and began consulting maps, I struck out ahead. Over here I'd found a polished axe crackled by an ancient fire, and, there, that whitish spot in a field was a fossil outcropping. Here again, as I briskly set the pace, a farmer had tried hiding an allée couverte under a huge manure heap, - and, oh yes, over there, by the copse we were approaching, my little daughter had curled up in the grass beside a field to take a nap next to a stone that looked like a pillow. A Neolithic grinding bowl! Which, when flipped, turned out to have a silken polishing basin, or portable polissoir, for polishing stone axes. I thought of it as the perfect tool for a couple: at the risk of stereotyping prehistoric sexual roles, a Neolithic woman could have ground grain into gritty flour on her side of the same stone that her men-folk polished their axes. I had noticed from examining fragments that such dual use of sandstone slabs had been so common as to be almost the norm, and fantasized that such tools might have meant as much as wedding rings.

Our guide caught up and I asked him if he’d probed the land that had recently become an adjacent golf course before giving authorization for the bulldozing, which had scalped the area. I just wondered because I'd checked the gouged and banked devastation and quickly happened upon a big celt and other refined tools a stone's throw from the megalithic tomb in the adjacent forest - in other words, precisely where I’d expected a habitation site. He looked downcast and explained that the political pressure had been so intense that he hadn't even dared enter the property. In fact, he said the regional archaeological service had had an exhibit in a large chamber beside their offices and had received instructions from the local politicos at about the same time to box it up - just for the weekend. The politicians explained that they needed the space for a "cultural event".

But afterwards, when the archaeologists began bringing the relics out of storage, they were told the space was no longer theirs. "You can't believe how beleaguered we are by the alliances of political parties and builders," the researcher said, "We were even forced out of our offices themselves."

As we entered the woods, we crossed a low earthwork which I speculated might be a remnant of a Neolithic ritual enclosure, given its length, positioning, and the importance of the covered alley on the plateau's headland. Speculating further, I inquired if he'd ever checked these woods for other megalithic tombs. No, nobody had done so, he admitted. “Why don’t we do it together sometime?” he suggested.

Then, crunching dead leaves in the late afternoon gloom, we arrived: a giant boulder chamber called "La Pierre Plate" crouched in its trench amid a vandalized fence, overgrowth and stirring trees. The "manhole" into this stone box had been carefully carved to contain a huge stone plug with an arched loop on one face - unnervingly like a 300-pound bathtub stopper. We crept through and squatted under one of the tomb's slabs to run our fingers along silken grooves and basins. The slab was another polissoir - this time a gigantic one that had been turned upside-down! Obviously the tomb’s makers had flipped it over to form the roof just as their Neolithic brethren had done at another covered alley at Janville-sur-Juine.

Such reuse of polissoirs intrigued me, and I suspected that it was not entirely coincidental, either in France or in other prehistoric cultures. For example, polishing basins are still visible on the backs of some of the largest Olmec heads, clearly showing that the heads were not made out of random boulders or blocks which had been quarried to order, but may have been reused polissors which had already acquired importance. In fact, the reuse of polissoirs in Neolithic cultures reminded me of the way Christianity built on the site of Roman temples or the way Islam converted the Aghia Sophia cathedral into a mosque. In any case, it seemed fitting that the Olmecs had transformed those most communal and utilitarian of stone artifacts - large polissoirs - into portraits of the first individuals to impose truly royal authority over their community. I wondered if there were examples of such reuse of polishing platforms in the rise of the first kingdoms elsewhere.

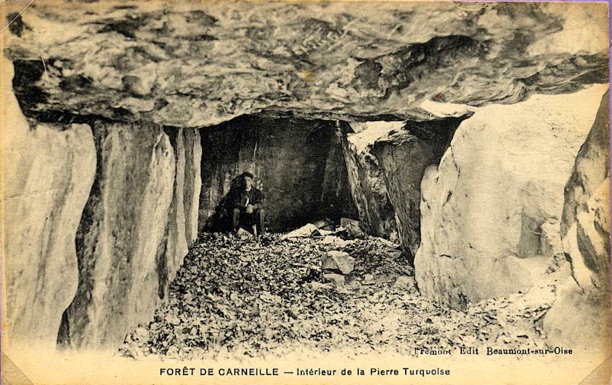

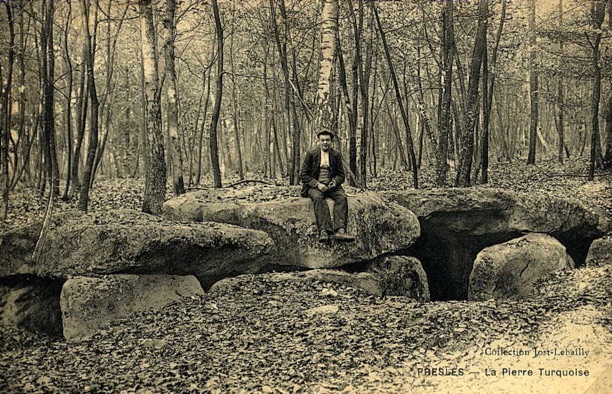

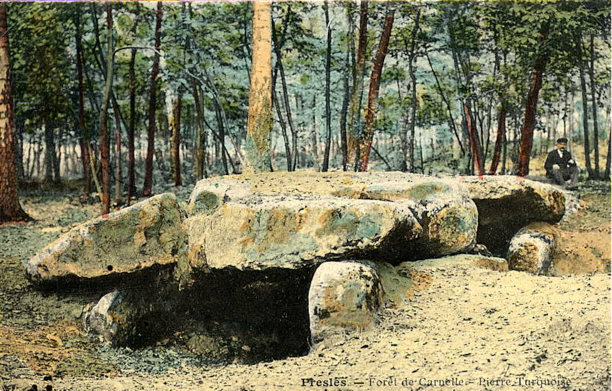

But now, the coach had to return, so everyone went off with it - except five diehards who were not about to quit while we were so close to the biggest Neolithic edifice in the region: a covered alley called the Pierre Turquaise, which hunkered in the forest just across the valley. Its megalithic chamber is so big that an 18th century nobleman used it as a kennel for his pack of hounds. As we hiked to it through the twilight, I made out a large charred spot on the roof stone. "Why, it’s been vandalized!" I cried, "someone's made a bonfire on the main slab!"

"It was an explosion," dropped an archaeologist from another jurisdiction, who was hiking beside me.

"What do you mean, an explosion! You know?"

"Actually, a bomb," she admitted.

"A BOMB! Why wasn't it in the papers?"

"It was kept secret. In fact, it was the Iranian-backed terrorists back in '86. They tested a bomb here before they killed all those people in restaurants and outside the Tati department store. The powder residues were identical to those from the terrorist bombs in Paris. In any case, the main slab was shattered. Check it out: it was reconstructed out of fragments, resin, and reinforced concrete. But the standing stone at the entrance with the carving of the Neolithic goddess was pulverized."

So that's where she'd gone! I had searched for her in vain! I scratched the roof slab and, sure enough, it was a composite. But why on earth would archaeologists, police and other government officials have kept so discreet about this politically inexcusable vandalism as to make it all but secret? Not only had the terrorists committed random murder, but they had ignored thousands of square kilometers of empty fields, forests and abandoned quarries and purposefully sought out the most important local vestige of humanity's common prehistoric heritage - an edifice without any ties to our world's current ideologies and strife! As far as I was concerned, the Iranians could talk all they wanted about exacting revenge and exerting pressure on France to stop aiding Iraq during the Iraqi-Iranian War, but this had nothing to do with that. These terrorists had shown their scorn for any notion of human community by destroying the most imposing evidence they could find of a past that predates all modern hatreds and anchors everybody to common roots. That, it seemed to me, distilled their shamelessness as much as their wanton murders.

But why the “discretion”? Because France was already negotiating with Iran and sought to quash non-lethal incidents that might exacerbate the public's fury? No, there'd been too many people in the know; I thought it was probably because of another phenomenon: namely, the fact that many French people enjoy guarding a juicy but open secret - open, at least, to the elite - that proves they are included in a charmed circle. For example, everyone "in the know" knew about President Mitterrand's "second" family and "natural" daughter, but none of the journalists in the loop breathed a word about it to the rabble.

Or else, might it have been due to another phenomenon illustrated by an anecdote that a reporter had just told me: he'd wanted to write about the plight of mountain gorillas in Rwanda amid mines, genocide, anarchy and unleashed poachers, but his employer, a powerful press agency, quashed the article because a story about the plight of mere "animals", when millions of people were being ruthlessly hunted, was seen as being in bad taste. How perverse we moderns are, I thought, with our brutal ideologies, gloating secrecy, and hypocritical compassion.

Mulling such raw notions, I announced I could find my own way to a train station and, splitting from the group, set off through the forest to relocate a row of giant slabs that I’d found years before in a mound of irises. Animals had tunneled all around the stones into the hollows below. Night fell as I stood on top of what I hoped was a still untouched monument from the depths of time. The forest stirred.

And complications fell away.

© 1996 Duncan Caldwell

Please click on the following thumbnail photos, which I’ve used as icons, to see the web pages or PDFs described in the captions.

Prehistory home page

This article is the first of two about engravings at a megalithic complex around a menhir, which is known variously as le menhir du Paly, la Pierre Droite and la Pierre du Paly, where I discovered a face on the east face and fingers and other anthropomorphizing features of a motif on the west face that had previously been interpreted as a Christian cross. These observations, which are split between the two articles, proved this article’s contention that the motif was actually a cruciform Neolithic “idol”. The paper goes on to describe a Neolithic frieze, which I found in a nearby cave (Butte de Châtillon 5). The panel contains such unique symbols as upside-down axes and an inverted axe surmounted by a U-shaped motif. If the U is like the ones that were engraved in dolmens, where they are often accompanied by mounds which seem to symbolize breasts, then it probably represents horns or the necklace of a Neolithic “goddess”. (Art Rupestre : Bulletin du GERSAR n° 62 - juin 2012: 33-38)

The Foz Coa / Coa Valley prehistoric rock art scandal

Prehistoric Art Emergency & Foz Coa / Coa Valley home page

The “prey-mother” hypothesis concerning Paleolithic feminine imagery & venus figurines

Key words: Neolithic funerary monuments, dolmen, dolmens, Neolithic funerary practices, Neolithic mortuary practices, Prehistoric funerary rituals, French prehistoric sites, Prehistoric sites in France, Vandalism,